Bulletproof released its first ever feature documentary, MOLDY: learn about the risks of toxic mold exposure in your environment by watching it here now.

MOLDY is the culmination of years of Dave’s journey – not to mention the research, interviewing, filming, production, and hard work that went into producing the documentary itself!

But MOLDY is just the beginning of something new. There’s a lot more to be done as people begin to learn about this hidden illness. If you’ve watched the movie and want to dive into more of the nitty gritty moldy details, this is the post for you. And remember to:

- WATCH THE BULLETPROOF RADIO VERSION OF THIS INTERVIEW, Episode #126!

- WATCH THE NEW MOVIE “MOLDY”, Screening online now!

Read more in this excerpt from friend and colleague Lisa Petrison at ParadigmChange.me, as Dave Asprey and Dr. Ritchie Shoemaker brainstorm how to further the research behind the science of mold toxins:

Dave Asprey and Ritchie Shoemaker: A Brainstorming Session on Furthering the Science of Mold Toxins

By Lisa Petrison, Featuring Dave Asprey and Ritchie Shoemaker, M.D.

Editor’s Note: Two of the leading voices in the effort to bring awareness about the dangers of mycotoxins to the public have been Dr. Ritchie Shoemaker (focusing mostly on mold in buildings) and Dave Asprey of Bulletproof (focusing especially on food mold and now the producer of a new movie on environmental toxic mold called “Moldy”). In this engrossing discussion (slightly shortened here from the podcast released last year), they discuss the mechanisms of mold toxicity, the reactions that some people report getting from molds in foods – and a planned proof-of-concept study to show that the amount of mold toxins in U.S. foods actually is causing people harm.

INTRODUCTION

Dave Asprey (DA):

Dr. Ritchie Shoemaker changed my life because he wrote a book called Mold Warriors.

If you’ve been listening for a while, you know I had Lyme disease and you know I’ve been exposed to toxic molds and you know I’m a bit of a canary. It was Dr. Shoemaker’s explanation of complex inflammatory pathways in the gut along with some treatment modalities that led me, in part, to recover a lot of my health.

So the knowledge that Dr. Shoemaker has put together through working with biotoxin illnesses throughout his career is impressive and almost shocking, when you hear about all the work he’s done.

Dr. Shoemaker, your most recent book is Surviving Mold. It also is a profoundly good book even for those who are not sick with mold today, on how to build a house that’s appropriate. It is an honor to have you.

Ritchie Shoemaker (RS):

This is going to be fun. We’ve got a lot of good energy to share today.

DA:

You’ve written several books on mold. Tell me about Surviving Mold, the most recent.

RS:

I had so much that I had learned since I published Mold Warriors in 2005 and there were so many pieces of the puzzle that were left out that it was pretty clear that it was time to try to put some time into expanding careful attention to detail into remediation, and looking more carefully at how in my mind U.S. agencies let us down in terms of proper evaluation of sick people inside water-damaged buildings. It was time to say what the status of treatment was.

In 2010, when I published Surviving Mold, we were just getting started on the paper on vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP). Since that book was published, we now have 18-month followup on our VIP cohort. We picked the worst folks.

With VIP, we had two questions. Does the drug work, long term? And is it safe, long-term? The answer to those questions was, yes.

We were able to show rather phenomenal safety. We found some problems with VIP that you can’t use it for this, and you can’t use it for that, if you have pre-existing conditions of different types. But if you met all the criteria, VIP truly was just what the doctor ordered.

When Surviving Mold came out, it was like, “This looks pretty good.” Now where we are is, “Geez, how can we let people walk around without regulation of inflammation from things like VIP?”

We’re using VIP in some hands of docs who are not retired, frankly, to overcome some additional obstacles. We’re looking at those to create races of supermen.

No kidding.

You can improve exercise tolerance. You can improve cognition. It is genomically active. We can look at fingerprints of what inflammation is doing not just in your brain, but also in human gene expression.

The next book is getting ready to come out maybe this coming year. It’s going to be looking at now that I’ve looked death in the face from my own illnesses from mold, and that fortunately has left me alone for a bit, where do we go from here?

Where we go from here is inside the human genome.

MOLD AND GENETIC MAKEUP

DA:

What percentage of people are particularly sensitive to mold?

RS:

We have collected statistics on over 10,000 cases and 2,000 controls. We’ve looked at the genetic makeup that these folks have. The immune response genes or HLA DR are a series of genes on Chromosome 6 that are understudied but remarkable in what they are doing as far as of taking a foreign particle — an antigen — and processing it so that our immune response can make an antibody to it.

And in this group of HLA DR, we see consistently that 24-25% of people cannot make adequate antibody responses, and they are the ones that comprise over 95% of people who have an illness from water-damaged buildings.

Now, you’re going to say, 95% is not 100%. But biology’s not 100%. You can get sick without HLA susceptibility. But genetics is huge.

DA:

In my experience, being the one in four who gets completely whacked upside the head by a moldy environment – all of a sudden, life falls apart. I remember going to the doctor and saying, “I feel like I’ve been poisoned. Nothing works. I’m wrecked.”

The other people though, they go into these moldy environments and they mount an immune response. But that comes at biological cost. It comes out of their cognitive function first, and then maybe they just get a cold. But they get a response that isn’t free.

None of us are healthier for being in moldy environments. Some of us are resilient than others, but by removing this from the environment, you free up resources to do something else useful with life. That’s part of the whole Bulletproof thing.

RS:

That’s absolutely important information. When people have some so-called minor symptoms with acute exposure that resolve with removal, we might say, “You had an allergy, or you had this or that.”

But basically what you had, with your idea of being Bulletproof, is that you were shot and hit. Now granted, you were hit in some sort of kevlar vest, so you were knocked down on the ground and you got up. You’re not dead. But you were hit.

DA:

That’s perfectly said. I work with people who don’t have those genes, or at least they don’t appear to because they can go into places that would give me a full hit. My forehead swells up and I feel like crap, and I go through a detox protocol.

They still don’t do as well. It’s like, “Oh, I’ve got a headache and I got a sore throat, but I’m fine the next weekend.” They’re back in the saddle without taking activated charcoal or anything else.

FOOD MOLDS

DA:

So for breathing molds in water-damaged buildings, one in four people are at serious risk, and the rest have various degrees of decline. What about food molds?

RS:

In litigation, one of the common ploys of defense interests who are trying to say that the apartment that was not taken care of properly — the mold on the shoes and the mold in the kitchen and the mold in the closet. They say, “That’s not the problem. Yes, there was an illness, but it was all from eating mold.”

You had a group of practitioners of the American College of Environmental Medicine that said, “No, mycotoxins need to come to a certain level to make people sick.”

And then they say, “Because you never get to that level, the illness comes from ingestion.”

So that was one of the ploys that I had to refute as an expert in mold litigation.

Fortunately, there’s a tremendous amount of really exciting information still coming out. The USDA is looking fairly hard at mycotoxins in animal feeds.

How much does pork make you sick? We should do that. But also along the same way, what can we measure within 15 minutes?

The classic example of hyperacute changes comes from measuringTransforming Growth Factor beta 1 (TGF beta 1).

When we want to see if a guy’s going to tolerate VIP or not, we’ll measure his labs at baseline and then give him a single dose of VIP. We track symptom changes, which usually will occur at 5 and 10 minutes, and then repeat the blood analysis at 15 minutes.

If TGF beta 1 goes up, guess what! That person’s coming from a moldy environment.

So if we take your pork experiments and add to that one that has been shown to work, I think it would be doable even before the genomics comes out on the market.

DA:

Wow.

RS:

It’s worth thinking about.

DA:

I would pay for my own studies for that sort of thing, just to have that done. It’s N=1. But the whole point behind Quantified Self and Citizen Science is that N=1 is pretty damned valid if you’re that one – and that it’s probably useful information for others. Then they can do their own N=1, and at a certain point we have enough data.

There is, for instance, in the pork case epidemiological data from eastern European countries about the levels of this toxin in pork and the incidence particularly of kidney and bladder problems. We understand some weird things about how that toxin smoothes out the inner wall of the mitochondria, so that you get mitochondrial damage from mold. That is separate from the VIP to leptin to insulin resistance pathway that builds up. I think that’s one of the reasons that I weighed 300 pounds, because I was living in a house that had mold in it.

MOLD RESPONSES

DA:

It’s fascinating to look at, because this is all sort of hidden. Number 1, you don’t know you’re in a moldy environment unless you become sensitized, as I certainly have been and other patients have been.

Also, you can be having symptoms that happen a day or a week later. For me, the way it feels is this.

I was on a dinner cruise in San Diego. The ship smelled like a mop. I knew it had mold in it, but I wanted to spend some time with the people there. So I said, all right, I’m going to take a hit.

I forgot my glutathione and my charcoal – I do well when I take those and am exposed to mold. I just didn’t have them with me on the trip.

I came out of it and four times the next day, I forgot a word. “What was I going to say?” I don’t ever drop words. My brain works all the time. So I noted that, because it was weird.

The day after that, I started getting really tired and my GI stopped working.

The day after that, I started getting skin lesions, like deep pimples and things like that. And canker sores in my mouth. Then I needed to sleep 12 hours. I just felt like garbage until I took a bunch of targeted supplements.

So I know my response curve. First it’s brain, then it’s gut, then it’s skin.

Also, I grew love handles the next day. In fact, I grew breasts. I posted a picture showing that I had swelling in my breasts. You could see my nipples in pictures that looked weird.

What’s going on from an inflammation perspective?

RS:

One of the really important issues is change in cell membrane permeability. We know that with NeuroQuant, that we can look at changes in some structures of the brain where they develop microscopic interstitial edema. That is a long way of saying that you can’t see this swelling of a brain area with an MRI, which is macroscopic.

This is microscopic, where the swelling is between the cells. So you have increasing leakiness of the blood-brain barrier. Fluid and plasma and particulates will move into particular areas. So you can sum as a whole, say, enlargement of a forebrain, but it’s happening on a microscopic basis.

The changes hyperacutely in brain clearly are due to blood-brain barrier permeability changes. VEGF, MMP9, TGF beta 1. There’s really good literature to support that. That’s one reason that we measure those.

It’s kind of interesting that we also know that TGF beta 1 induces production of compounds that block correction of brain damage after the fact. So if you have traumatic brain injury, if you’ve got concussions and all this stuff, you start making this stuff called glial fibrillary acidic protein. That stops the reassessment of interactions of these fibers called Purkinje fibers in the brain.

So not only is there an acute injury, but that acute injury is multiplied by a genomic change in the gut much quicker. I thought that you were going to say that your gut was coming before your brain.

DA:

I feel it in my gut, but I don’t get bad gas and diarrhea and all that. I just feel that my stomach’s like, you ate something bad. I know, but there isn’t any external sign.

RS:

Some of the best work done on so-called “leaky gut” has come out of the celiac groups that look at tight junctions. The same tight junctions that are part of the blood-brain barrier are paralleled — analogous but not exactly the same structures — in the gut.

Those are loosened rapidly — especially if you’re low in melanocyte stimulating hormone (MSH). So if your MSH is cooked — and most folks that I see are — specifically, your predisposition to develop hyperacute changes in GI is multiplied.

Added to that is the tremendous increase in bile salt production, hyperacutely. This is one of the things that we as bile flow is slowed by an inflammatory response. Bile salt production gets upregulated in an attempt to move bile along.

That doesn’t work. Then you get sludging of bile and reflux of bile back into the stomach and lots of misdiagnoses of what’s wrong, with abdominal pain and bloating and belching.

But specifically, as those bile salts move down further in the gut, they can add synergistically to loosening of some of these tight junctions in jejunum and ileum. So it’s not just one element.

CYANOBACTERIA

RS:

I want to go back to the confounders. You know full well that in a moldy building, you’ve got bacteria, you’ve got actinomyces. Well, show me an animal factory, like a pig factory, that doesn’t have some kind of lagoon around full of particular kinds of nutrients.

And guess what grows there. Cyanobacteria. A huge problem in North Carolina, for pigs and chickens both, is that many of these lagoons now are full of cylindrospermopsis and microcystis. That adds to the inhalation of pigs of what’s growing out in the lagoon.

DA:

People who aren’t familiar with your work should know that you got started being an amazing medical detective looking at what happens with these toxic blooms of algae and how they create toxic neurotoxins that survive and can enter the water supply and have killed people by causing this sort of inflammation.

So you are saying that that original work now is illuminating what is happening at industrial animal farms where they are allowing this to happen. It is airborne, correct?

RS:

Yes indeed. Now the particular cyanobacteria toxins will be volatilized in association with water droplets. So they’re not evaporating. But they are in the air. You can breathe the air over the body of water. The wind can blow it.

In Florida, at Lake Apopka, there are people having a measurable amount of microcystin in sixth floor condominiums, 250 yards away from the shore of the lake.

We had the same problem with a guy in Wisconsin. You could say, “Wisconsin’s a hotbed for microcystis, it’s 50 degrees below zero there now.” But between this guy’s apartment and Lake Michigan is this beautiful lagoon full of blue-greens.

Here you are in California with people eating blue-green algae for health benefits out of Klamath Lake. And Klamath Lake had a big outbreak of microcystis. So it’s like, wait a minute, this just doesn’t make a lot of sense.

As you go forward, since we can’t measure microcystin in blood, I would love to give you some summer pork, and start to try to measure some of these things in addition to the proteomics.

CHICKEN

That would be fascinating. I would be happy be a guinea pig, and I know how to get myself back in the saddle within two days even if I eat the world’s worst pork. Wow.

RS:

I thought you were going to tell me that chicken was also doing things to you.

DA:

I just don’t eat chicken. It’s gross and it’s full of bad Fusarium from the corn. Chicken’s not a good source of polyunsaturated fats either.

RS:

It’s even worse than what you said.

One of the problems with little baby chickens and little baby pigs both is that they suffer from a parasite — not a babesia, not a toxoplasma, but another one from the malaria family, called eimeria. Eimeria kills little chicks like crazy. They’re only 10 cents a piece, but that adds up if you’ve got 40,000 chickens.

So they put Monensin and Nigericin, which are polycyclic ether toxins, into chicken feed, to make sure that you kill the eimeria parasite, before it starts growing in the baby chicken.

What these compounds do: they, in association with receptors that will pick up mycotoxins, are phagocytosed or engulfed into antigen presenting cells. Monensin and Nigericin — same with insulin receptors that are internalized — will prevent release or opening of this endosome, as we call it. This little goodie that comes to the antigen presenting cell that you need to stick an antigen on to recognize — they will prevent that release.

So if you are wondering where your Type 2 diabetes came from out of the blue, my question is, did you listen to all those people who said, “Eat more chicken and less beef”? Because now you’re eating Monensin and Nigericin, which will create insulin resistance because you sequester insulin receptors and insulin inside antigen presenting cells.

The same thing happens with mycotoxins. And in fact, Monensin is one of the things that protects against some mycotoxin poisoning if you are eating that at the same time you’re eating stockpiled foods.

And what other compounds are in these foods that we don’t know about? Can you tell me where all the strontium is coming from in the Pocomoke River?

Or what we are doing with arsenic, saying it is a growth stimulant? It used to be put in chicken feed all the time, and now finally it is being taken out.

But what is this stuff doing, getting in the chicken that we eat?

NEED FOR DATA

DA:

It is not something that I prefer to put in my body. I decided a long time ago that when I go out to eat, if it’s not grass-fed pastured stuff, usually from small farms, I will eat a vegetarian, soy-free, corn-free, grain-free meal. In other words, I bring my own butter, and I put it on top of a whole bunch of steamed vegetables. And maybe if I feel like I want carbs, I’ll have some white rice, which has had the outer layer where the mold toxins are polished off. Not to mention the other naturally occurring toxins that occur in the outer layer of the brown rice anyway.

It sounds like I’m totally a nut, except that there are thousands of people who are as picky as I am now, because they tried it once and their skin cleared up, they lost weight, they stopped being inflamed, their brain cleared up, and they’re just dialed in.

And then there are a bunch of other people who tried it and they just felt really good all the time instead of feeling highly variable.

So I think this is a much bigger problem in the food supply than anyone talks about. Am I just being picky here?

RS:

The issue that I face is that we need data.

If your N=1 study is added to another N=1 study, then let’s get N=100. There are mechanisms to do that, but we really do need to follow the principles of science.

So it’s one thing for you to share what you know. But I’m going to make the pitch that what you know needs to be looked at as carefully as anything else. Otherwise you could be just some kind of wacko, spouting off on the radio.

But if instead you are a prophet, as I suspect you are, then what we really could do without too much trouble is develop a research design, find some funding (it shouldn’t be too expensive), and actually look at this.

DA:

How much funding would something like that cost? I’ve never done something like that.

RS:

If we did this right, I would imagine that $25,000 would do a study that would be enough to show evidence that there is a problem. So it’s not zero. That’s with people donating their time, just paying for labs and supplies.

DA:

Hmmmm.

RS:

The answer is going to come with genomics. If we had a pilot study that said, “Yes, I showed these hyperacute changes in people who have exposures,” then we want to look at chronic low-level exposures. People who eat chicken all the time. People who eat pork all the time. People who think they’re getting older and that’s why they can’t remember where they left their hat yesterday.

That’s when the genomics will tell us what their fingerprints are. Out of 25,000 genes, for example, we’ve got 350 of them fingerprinted for mold. I can tell you with one tube of blood whether you’re moldy or not.

Same thing with the NeuroQuant. We can look at your brain the same way. If we put all of these together, now we’ve got these interacting, disparate, independent variables with one conclusion.

And that’s the food did it.

DA:

I will work on ways of putting something like that together. I think there’s probably enough demand to do a Kickstarter or something, where we get enough people who are interested to contribute a little bit and do a study.

I have zero doubt that this is a problem. I’ve seen it in pro athletes, people who aren’t mold sensitive but they’re just off their game. It’s smaller changes.

So I’m on board with it. We’ll figure out how to make something like that work.

RS:

It’s called a proof of concept study. As such, it’s not going to be double-blind, placebo-controlled. It’s not going to be anything other than one data set from one group that we compare to known controls.

We’ve already got the data on controls. We don’t have to re-invent that wheel.

So much of what I see written about mold just does not have any control groups at all. You can’t do anything about conclusions, without control groups. But we’ve already got them.

So if your ideas are solid, and let’s assume for a minute they are, then we can show unequivocal objective parameters — and not just that I had trouble finding a word four times on Sunday.

DA:

There’s no doubt that science backs this up in my mind. And if it doesn’t, then there’s something else going on. What I’d do there is that I’d say, “Let’s look at the gut. What’s the gut biome look like? What are the bacteria that are growing in your stomach and how do those interact?”

I’ve read research about how those break down certain mycotoxins. So there may be another set of data that we need there.

But the effect is there for me and for enough other people that at this point, with the amount of specificity from the people I’ve talked with, I don’t think it could be placebo.

RS:

One of the things that I’m hoping that you’ll do as you consider doing this is looking at changes in gut bacteria. If we are looking at bacteria and fungi and any kind of compounds that will break down mycotoxins in the gut.

DA:

Ubiome is one of the genetic studies of the gut. I’ve been working with the Ubiome guys.

RS:

Jeremy Nicholson in the UK has been one of the pioneers, looking at metabolites present in urine that do change fairly hyperacutely.

So maybe some of that $25,000, we can spend on urine specimens and Jeremy can help us out. It would not be surprising if that turned out to be easy, quick and reliable.

MOLD AND THE GUT

DA:

Let’s talk for a minute going back to celiac. One of the things that toxic molds can do is to cause your immune system to cross-react with gluten and casein. So when you’re exposed to the molds, especially airborne molds, you become more sensitive to gluten and casein.

And we know that in people with Crohn’s disease, that there’s a much higher likelihood of them having circulating aflatoxin in their blood.

Do you think that there is a correlation between celiac/Crohn’s/IBD and mold toxins?

RS:

If we asked the question a different way and said, “Is there a chronic inflammatory response syndrome that can be applied to food tolerances?,” the answer is yes.

Now the food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome, FPIES, is clearly shown to be some of the most food intolerant people, whether it’s corn or soy or casein or lactose. Some of these kids are just wiped out, can’t eat much of anything. If they’re nursing and mom has a Fig Newton, the kid suffers terribly, for example.

But specifically, that is related to an inflammatory process associated with exposure to water-damaged buildings. We have a nice case series along that way.

Crohn’s is a little different in that it is a chronic inflammatory response syndrome without the same contribution with C4a and MMP9. There we see TGF beta 1 and T regulatory cell imbalances dominating those people. That’s a separate issue, that we know it’s inflammatory, but we can’t necessarily blame the initiator as exposure to a water-damaged building. So there are two different issues along that way.

I just want to throw out for discussion three different ways to get gluten problems.

One is with true tTG IgA positive celiac disease.

The second is MSH deficiency. There’s a nice paper from James Lipton and Anna Catania looking at MSH residence sites in the gut. And it’s everywhere. When you don’t have MSH, regulation of autoimmunity and autoimmune problems in the gut starts to fail tremendously. You will see loosening of these tight junctions and gluten actually localizing in the tight junctions whereas before it didn’t.

The third group of people I haven’t figured out, and I’d appreciate your comments in this regard. They just can’t handle gluten at all. They don’t have antigliadin antibodies that the MSH deficient people will have. They don’t have tTG antibodies. But if you give them gluten, they go to hell in a hand basket. So the real issue for them is: I’m sorry, medical science doesn’t have the answer why, but for now, you’re stuck and you can’t have it.

DA:

Could it be a gluteomorphin effect? The opiate effect that comes from improperly broken-down gluten going into the brain and they feel like crap?

RS:

Reasonable question. I don’t think anybody has even looked at that. As far as the effect of any gluten compounds in the brain, if there is published data on that, that’s not something that I’ve read.

A LINK BETWEEN AUTISM AND MOLD?

DA:

I believe there is some research on that. I reference that, I think, in my “Better Baby Book.” Also, I’m giving a talk at the Autism One conference coming up here. I’ll be talking in part about mold and toxins and things like that. Also, Dr. Tom O’Brien who put on the “Gluten-Free Summit” has spent years looking at autoimmune responses to gluten. We’ve also had some conversations, both about mold cross-reactivity to gluten as well as that opiate effect of it.

RS:

I would love to learn. There are so many holes in my knowledge that when I listen to smart people tell me things I’ve never heard of, the answer is, “Feed Me, Seymour.”

If you ask someone like me to comment about something that I don’t know about, I’m not going to be of any help to you. But if you take a proof of concept study and you put two things in, and neither one is known to be related, you’re going to lose any credibility for that study. So pick one and follow through with it.

For autism, I don’t think mold is causative, having seen a small number of autistic kids, maybe 100 or so. But I know full well that if you take an autistic kid and you make him moldy, you sure make his autism worse. So inflammation is not a friend of the autistic person.

DA:

I believe there is chronic autoimmune inflammation in autism. It’s hard to know exactly what it is that pushes the immune system over. Sometimes it may be mold, sometimes it may be mercury, sometimes it may be some other stressors. But something happens that pushes you over, and it’s usually a cumulative burden.

So I wouldn’t say mold is causative. But I think in some cases, particularly one in Huntington Beach, it sure looks like it. A court even said it was causative.

But it’s one of those things where it’s certainly not beneficial for anyone on the planet, and it’s much more harmful to some than to others.

WHEAT, CORN, SOY, COFFEE AND MYCOTOXINS

DA:

Now let’s switch gears a bit and talk about things like wheat, corn, soy, coffee. What’s the mycotoxin risk, in your experience?

RS:

We have looked at aflatoxin as our target, and have not looked at stored wheat or stored corn or stored coffee.

In answer to one criticism of my ideas in deposition, I had 10 people who were really good folks and willing to go along with a wacko idea. I asked them to eat as much peanut butter in a day as they could. On average, it was about six pounds of peanut butter per person.

I had Skippy.

We looked for evidence of aflatoxin poisoning, despite FDA regulation and rules and limits. We found no change in any of the markers that I could look at in blood.

That was not proteomics. It was a limited number. It certainly was not genomics.

In all of these ideas that you have, whether it’s coffee or anything else, any assessment has got to include glutathione. Glutathione deficiency, I think, is overstated. But there are some docs that swear by glutathione.

When we look at the effect of glutathione supplementation — whether it’s by injection or tablet or under the tongue — and try to show measurable changes in proteomics, it isn’t there.

Glutathione is cited repeatedly as contributing to breakdown of mycotoxins in gut and duodenum. Mycotoxins might be there, but do they get out of the stomach – and with patulin we know that a small percentage will – and if they get out of the stomach, if they get bound to a receptor that binds onto a free acetyl group, if they are engulfed by an alveolar macrophage, for example, or an antigen-presenting cell, and Monensin’s around, that mycotoxin will go inside of the cell and the cell will die. This idea of programmed autophagy is one of the cell basically killing itself. Apoptosis goes along with that.

But basically, looking at the organelles of a cell as a defense mechanism. Because some cells will take things that we can’t metabolize or can’t process, suck them in, and then the cell gets chewed up.

So that becomes a mechanism to destroy things.

DA:

We use intermittent fasting on the Bulletproof Diet in order to increase autophagy.

RS:

Along with that, I don’t know what microbes in the gut are going to break down mycotoxins. These are energy-rich compounds, they’re carboxylic acid esters, lots of energy tied up in double bonds. Man, this is fertilizer for somebody.

GLUTATHIONE

DA:

I’ve seen studies on which species break down different mycotoxins. It’s complex.

For cognitive function purposes, I feel a noticeable difference on glutathione. I make a liposomal glutathione with a lactoferrin molecule in it, so it absorbs through the gut lining. So it’s an extreme bioavailability version of it.

When I’ve been exposed to a moldy indoor environment – less so from just food – taking five doses of it makes my brain feel better. I can start thinking again relatively quickly.

Separately from that, I take charcoal, I take cholestyramine, I take a bunch of anti-inflammatory stuff to knock the inflammation down in every pathway that I know of. And I increase glucuronidation with calcium d’glucarate.

RS:

If you have a stable program and you know that this nifty liposome that you make is reliable, that is an even quicker and less expensive proof of concept study to do.

For all the environmental docs who love glutathione, I keep saying, “Where’s the data?”

Bill Rea [Dr. William Rea of the Environmental Health Center in Dallas] had some data. He had multiple variables thrown in at the same time. But if you don’t control for multiple variables simultaneously, what do you have? Nothing.

Bill Rea’s stuff works for some of the worst patients I’ve ever seen. He has glutathione, he has saunas, he has allergy treatments that he makes up. He’s a really bright guy.

But at the same time, if someone like me comes along, who’s not as bright as he is, and says, “I’m going to try this too,” can I reproduce what he does if I don’t have something written down in a cookbook? That’s the whole idea of having protocols.

That’s where I come in, to say, “Look at you. You’ve got individual variation up the wazoo with what you’re doing. How do we know that liposome’s what’s making the difference if you’ve done four interventions at the same time?”

But there are answers. And it’s your enthusiasm and your youth that will contribute to getting these kinds of answers out there.

DO TREATMENTS WORK?

DA:

The single variable testing is really important. But what I’ve discovered is that you’re not going to bake a loaf of bread by baking the yeast and then baking the water and then baking the flour. You’ve got to mix stuff together in complex system in order to create a result.

What I tend to do for something like inflammation is that I put everything in that I can think of. Then I pull single variables out to see if it stops working.

Because if there are five things causing inflammation and you pull out just one, you oftentimes won’t see it. For instance, you’re allergic to casein and you’re allergic to gluten. If you pull just one of them out of the diet, you’re probably not going to see significant results at all. If you pull them both out at the same time, suddenly everything changes.

So the complex interaction of our gut biome and the external exposome (the mold and other things) makes eliminating single variables easier than introducing single variables, at least for getting rapid results.

RS:

In 2004, at the beginning of the Chronic Fatigue Syndrome meetings that were held in Madison, Wisconsin, I gave the first talk of the morning and said, “Whatever you do, do one intervention at a time. Record data and be very precise.”

Jacob Teitelbaum gets up after me and said, “Ritchie, science is fine, there’s nothing wrong with it, but my patients want to feel better, so I do everything all at once.”

There still is no clear assessment about whether Jacob is right or I am right. But if Jacob is doing is going to be sent to many people with heterogeneity of genomics, heterogeneity of genetics, heterogeneity of inflammatory responses, he’s going to find that some people get better, some people get worse and some people have no change. But he’s not going to know any one of those three.

Your idea is a variation of that, which is to remove one at a time.

For example, it’s very common for people that I see who like to take supplements to take 20 different kinds of supplements at a time. I say, “Okay, do you know that your silymarin is actually helping? Have you stopped it to see if you felt worse?” And they say no.

Then I say, “Let’s get some of the inflammation cleared up. Then take your supplements one at a time and remove them.” To do basically a repetitive re-exposure trial.

We take you off it. Do you get worse? If so, we put you back on it. Do you get better?

Or if we take you off something and you get better, then if we give it back to you, do you get worse?

With the foods, you are taking away casein and seeing if they get better, and then putting it back to see if they get worse.

So I think you are trying to address things in a more scientific manner than saying, “Take 20 supplements at once and I’ll see you next year.”

DA:

It’s a frustrating thing. The practitioners that I work with know that people get better on the supplements, but they don’t always know exactly that this is the one that did it.

I decided a long time ago that one of the cheapest things that I could have was expensive pee. I know that some of the supplements that I’m taking right now might not be doing something. But I also know that what I eat, what I breathe, whatever else I’m exposed to, the level of stress that I’m under, at some point those things will change.

Having the raw material there probably isn’t harmful. If I can find research that it is, then I’m probably not going to take that vitamin.

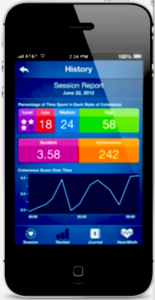

Heart Rate Testing

DA:

The notion of biohacking is to use devices to track how we’re doing. I’m advisor for the Heart Map Institute. Is heart rate variability a good measure for whether those supplements worked or not?

Because heart rate variability is a pretty neat short-term sign of whether the sympathetic nervous system is under stress. And my sympathetic stress goes way up when I am exposed to toxins or when I’m having a hard time excreting them.

RS:

If we look at exposures, we know that for some people affected by a water damaged building, there is going to be a rise of pulmonary artery (PA) pressure. That means it’s harder for the blood to get from the right side of the heart to the lung, which means that the blood coming back from the lung to the left side of the heart — which we call venous return — is going to be impacted.

If you are trying to do something, like go up a flight of steps, and you’ve got reduced venous return, maybe from an exposure or from the pork that you ate two days ago, what will happen is that if you don’t control for PA pressure, you will have a problem maintaining cardiac output.

So how do you increase cardiac output if you can’t increase stroke volume because of venous return problem? You increase pulse rate.

So if you’re going to look at heart rate variability, which is looking at pulse changes, you’ve got to control for PA pressure.

DA:

You can use heart rate to determine a food sensitivity. So your heart rate goes up by 16 beats or more on a regular basis.

RS:

If we know that you don’t have a rise of PA pressure with exercise, that’s an important variable to put in before you look at heart rate variability.

DA:

There’s heart rate, but if you look at the change in the spacing between each heartbeat, you’re getting a different signal there. So even if the heart rate goes up, if the sympathetic stress on the organism is lower, the interbeat variability will increase.

Basically, the spacing between each heartbeat should vary regularly. Even if you have a higher heart rate or a low heart rate.

FINDING COMMONALITIES

RS:

Once more, we need to put good controls in there. Good controls are the basis of good science.

Going back to the very important part of N=1, being very primitive in how I recorded data that was unusual in the past. I had a ziploc bag that sat right in front of my chart rack, and I had sticky notes of people with unusual conditions, and when I saw two, I had two of them written on the same sticky note.

This was the very sophisticated way that led me to understand about gastroparesis being so common in people who have chronic inflammatory response syndrome. We used to think that GI function that was diminished was confined with some incredulity thinking of our model to older diabetics with bad control. It turns out that about 10% of mold patients will have elements of gastroparesis.

But it was just one after another of these sticky notes in my ziploc bag that led me to say, “Hey, let’s look at it systematically.”

That was a collection of N=1.

DA:

The cloud computing stuff that I’ve spent most of my career working on has changed the N=1 game. We look at who are some people who have some similar observations here and then can organize little tests.

Before, we relied on you to notice this on your Post It notes. Now, it’s something that we can coordinate. We can even all look at our 23 And Me profile analysis and see what’s common between that. And there are groups doing that.

RS:

If you look at the genomics, you want to look at proteogenomics, because that’s so so much better. But that’s down the road.

If this cloud technology that you’re talking about is focused on a million people, there’s no end to the data that can be collected. And if the data is collected, someone is going to have the computer savvy to mine that data.

That’s where the world’s going to be.

MYCOTOXINS AS TUMOR TREATMENT

DA:

Is there a case that says that people should be eating food with mold toxins in it? Are there potential benefits?

RS:

Interesting question. I know full well that my incidence of people with low levels of VEGF is way way more coming out of moldy buildings than not. The incidence of cancer in those people is way way down.

If we look at the anti-angiogenesis movement that Judah Folkman from Children’s in Boston got started years ago, his insight looking at what stopped new blood vessel growth needed to feed tumors got started like the discovery of Penicillin. He left open a Petri dish with epithelial cells in it. It was Friday night and he comes back on Monday. All the epithelial cells were all ruffled and crinkled. They’re dying.

He goes, “Oh my God, look at this!” In the middle what was growing was a colony of Aspergillus Fumigatus. And Fumagillin was the first antiogenic agent that there was.

Now compare that to the possible benefit of reduction of anti-angiogenesis to aflatoxin, which is reported to be associated with liver cancers in China and Australia and everywhere else. If you look at the microcystin literature, guess where you find liver cancer increase with exposure. It’s China and Australia.

So are we looking at one variable of aflatoxin? Another variable, which is microcystin? Or some sort of interaction between the two?

DESIRE

DA:

These are things that I really want to know more about. In the meantime, my conclusion is that for people who are interested in being very high performing, there is no reason to intentionally eat even low levels of mold toxins.

I really like to feel good all the time. And the things that I can do feel good helps other people too. But we do need more science, that I am interested in funding.

RS:

The passion that I’m seeing in you and the desire to make things happen — to me, that’s an indispensable element. I hope you can find the funding you need and some colleagues to join along with you in your quest. This does not sound quixotic at all. It sounds like you have a chance to bring your insights to a far bigger population.

My concern is that my profession, being a licensed physician, includes a lot of people that don’t like to read. That don’t want to think outside the box. Physicians are even slower than politicians to learn things. Certainly the attorneys are quicker along the way.

As you go forward in your quest, always challenge your own thoughts and hypotheses from today. Challenge those tomorrow. That’s part of my Bulletproof world, to say, “Did this assumption that I made actually bear out?”

Another Bulletproof idea – thank you to Aldous Huxley – is casting out false knowledge.

ADVICE FOR PERFORMING BETTER

DA:

There’s one question I’ve asked every guest on the show. What are your top three pieces of advice for people who want to perform better?

RS:

The most important one comes from the Greeks, and that’s “Be true to yourself.” Being true to yourself means that you’re honest, you’re thorough, you look at things with rigor.

The second piece that I have to remember because I tend to say too much is, “The tongue is the enemy of the neck.” By all means, recognize who your audience is, what your audience is going to be saying and thinking.

And recognizing as well that if we ever want to look at any kind of social situation, you need to look to see where the energy is. For some people it’s sex, for some people it’s aggression, for some people it’s money, for some people it’s power.

In your case, I see the tremendous driver being knowledge. As that, I go back to the Aldous Huxley quote. As you refine your knowledge, and as you continue to cast out false knowledge, then when you have the understanding, you’re ready to go forward.

People can throw all the rocks they want, but your understanding will take the day and win it.

DA:

Wow, that’s awesome.

Dr. Shoemaker, thank you a ton for being on the show today. Do you have a website?

RS:

SurvivingMold.com is just filling up with really nifty things to look at. We’re bringing in writings from multiple other practitioners and providers. There’s a lot on remediation. There’s an awfully lot of free downloads. Frequently Asked Questions are important. People should really know what their visual contrast sensitivity test is and what that of their kids is.

VCS TEST

DA:

Let’s talk briefly about what a VCS test is.

RS:

If we look at the reduction of blood flow into certain organs, we can measure using MR spectroscopy rising lactate in the brain. But how can we measure the so-called capillary hypoperfusion elsewhere in the body?

We can measure directly velocity of flow in blood vessels in the retina and the neural rim of the optic nerve head. Reduction of flow will create a neurologic deficit in a function of vision that impacts what’s called contrast. That’s the ability to see a gray image against a gray background.

Contrast vision is one element of our neurologic function that’s affected dramatically and rapidly by capillary hypoperfusion coming from inflammatory responses. We can measure it, record it, use it as a monitoring device, show improvement with therapy.

Also it will show relapse if there is re-exposure. But it also will show us stability if there’s no exposure and treatment has been obtained.

DA:

So the translation of this is that this is a biohacking technology. By looking at the test and distinguishing between the fine shades of gray, you can tell something about the state of your brain that you otherwise wouldn’t be able to tell.

It’s pretty cool. I’ve used it myself.

RS:

I never have thought of that as biohacking, but you’re exactly right. Thank you for that. That’s cool.

MORE ON THIS INTERVIEW

Above is the video version of this interview.

More information about this interview (including the MP3 version) is on this page on the Bulletproof website.

Additional Resources:

To visit Dr. Ritchie Shoemaker’s website, Surviving Mold.

To go to the Paradigm Change website, please click here.

Sign up for occasional email updates about new Paradigm Change content and other news about the role of mold toxins in chronic neuroimmune disease here.